Ein Dauerthema der Klimadiskussion ist der sogenannte Hiatus. In der Geologie bezeichnet dies eine Lücke in der Schichtenfolge von Sedimenten, sozusagen eine Ablagerungspause. Im Bereich des Klimawandels ist damit die abschnttsweise ausgebliebene Erwärmung der letzten knapp 20 Jahre gemeint, also eine Erwärmungspause. Klimamodelle hatten eine stetige Erwärmung von 0,2°C pro Jahrzehnt prognostiziert. Eingetreten ist aber wohl weniger als die Hälfte.

Verfechter der Klimaalarmlinie bemängelten die Verwendung des Begriffs Hiatus, da die Temperatur doch in der Tat angestiegen sei. Es ist daher wirklich etwas problematisch, über den Gesamtzeitraum der vergangenen knapp 20 Jahre von einer echten Pause zu sprechen, so dass „Hiatus“ den Sachverhalt nicht genau trifft. Aber natürlich ist es Fakt, dass die Erwärmung der letzten 20 Jahre sehr viel langsamer ablief als von den Modellen berechnet. Dies ist das Hauptproblem, das es gilt zu verstehen. Es lohnt sich daher nicht, sich in einer wenig fruchtbaren Diskussion über Begrifflichkeiten zu verzetteln. Die Wissenschaft hat das nomenklatorische Problem bereits aufgelöst. Hier wird meist vom „Slowdown“, also der unerwarteten Verlangsamung der Erwärmung gesprochen. Aber auch „Hiatus“ wird teilweise benutzt, wobei damit das Erwärmungsdefizit gegenüber den theoretischen Berechnungen gemeint ist.

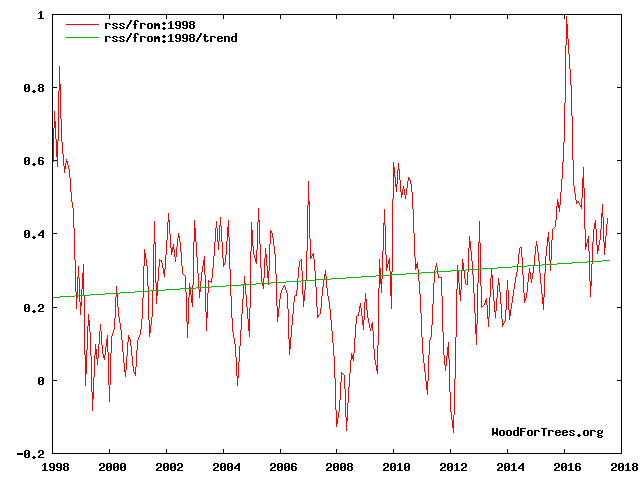

Jeder kann sich bequem selber die Temperaturentwicklung online plotten. Bei Woodfortrees wählt man den entsprechenden Datensatz aus, z.B. die RSS-Satellitentemperaturen. Dann wählt man einen Betrachtungszeitraum und ergänzt einen Trend. Fertig! Beispiel RSS seit 1998, also von El Nino zu El Nino (Abb. 1):

Abb. 1: Globale Temperaturentwicklung gemäß RSS-Satellitendatensatz.

Gut an der Trendlinie zu erkennen: In den letzten knapp 20 Jahren ist es wirklich nur um 0,1°C wärmer geworden, wobei eine Erwärmung von 0,4°C zu erwarten gewesen wäre. Diese Diskrepanz gilt es zu respektieren und zu erklären. Wie können die Modelle verbessert werden, damit sie wieder realistischere Prognosen liefern können? Einige Klimawissenschaftler, auch aus Potsdam, haben sich leider aufs plumpe Leugnen versteift. Sie behaupten irrigerweise, dass es gar keine Diskrepanz gäbe, daher nichts erklärt werden müsse. Journalisten machen leider viel zu oft gemeinsame Sache mit dieser kleinen Minderheit und bieten ihnen ein öffentliches Podium für ihre kruden Ansichten.

Glücklicherweise hat die Mehrheit der Klimawissenschaftler das Problem anerkannt und sucht bereits eifrig nach Lösungen. Es vergeht kaum ein Monat, ohne eine neue Veröffentlichung zum Thema. Im Juni 2017 publizierte eine Gruppe um Benjamin Santer unter Beteiligung von Michael Mann eine wichtige Arbeit in Nature Geoscience. Darin bestätigen sie zunächst den Slowdown, also die Verlangsamung der Erwärmung. Dann machen sie sich Gedanken, was wohl in den Modellen fehlen könnte. Dabei stoßen sie auf die Ozeanzyklen („internal climate variability“), deren Wirken man in den Modellen wohl in der falschen Phase erwischt habe. Wenn man sie korrekt eingebaut hätte, dann könnte man die Diskrepanzen der 1980er und 90er Jahre erklären. Den offensichtlichen Slowdown im 21. Jahrhundert kann man damit aber nicht erklären, da legen sich Santer und Kollegen fest. Bei Betrachtung der letzten 17 Jahre wird deutlich, dass wohl etwas in den Klimaantrieben der Modelle („external forcings“) nicht stimmt. Die Erkenntnis aus dem Munde dieser berühmten Wissenschaftler ist hochbedeutsam. Die IPCC-Tabelle des Strahlungsantriebs, dem Allerheiligsten der Klimamodelle, steht ab sofort offiziell auf dem Prüfstand. In unserem Buch „Die kalte Sonne“ haben wir genau diese Tabelle kritisiert: CO2 zu stark wärmend, Schwefeldioxid zu stark kühlend, Sonne zu schwach wärmend. Hier der Abstract von Santer et al. 2017:

Causes of differences in model and satellite tropospheric warming rates

In the early twenty-first century, satellite-derived tropospheric warming trends were generally smaller than trends estimated from a large multi-model ensemble. Because observations and coupled model simulations do not have the same phasing of natural internal variability, such decadal differences in simulated and observed warming rates invariably occur. Here we analyse global-mean tropospheric temperatures from satellites and climate model simulations to examine whether warming rate differences over the satellite era can be explained by internal climate variability alone. We find that in the last two decades of the twentieth century, differences between modelled and observed tropospheric temperature trends are broadly consistent with internal variability. Over most of the early twenty-first century, however, model tropospheric warming is substantially larger than observed; warming rate differences are generally outside the range of trends arising from internal variability. The probability that multi-decadal internal variability fully explains the asymmetry between the late twentieth and early twenty-first century results is low (between zero and about 9%). It is also unlikely that this asymmetry is due to the combined effects of internal variability and a model error in climate sensitivity. We conclude that model overestimation of tropospheric warming in the early twenty-first century is partly due to systematic deficiencies in some of the post-2000 external forcings used in the model simulations.

In wenigen Wochen werden die Autoren für den neuen IPCC-Bericht nominiert. Ob sich diesmal der Realismus durchsetzt und die Probleme in den Klimamodellen und Prognosen ergebnisoffen und nachhaltig angegangen werden? Oder geht es wieder nur um die Vermeidung eines Gesichtsverlustes? In der letzten Ausgabe des Berichts (AR5) wurde beispielsweise bei der CO2-Klimasensitivität kräftig getrickst, der wichtige Mittelwert einfach nicht angegeben. In jeder anderen Sparte des menschlichen Tuns wäre dies unmöglich, denn der Mittelwert bzw. bester Schätzwert wäre unverzichtbar. Nicht so in den Klimawissenschaften. Dort kann man nach monatelangen Verhandlungen zur Frage nach dem aktuellen Wochentag sagen: „Irgendetwas zwischen Montag und Freitag. Aber auf den Tag heute wollen wir uns nicht exakt festlegen“.

Wie bei den Boxweltverbänden, gibt es auch bei den globalen Temperaturdatensätzen eine ganze Pallette von konkurrierenden Systemen, darunter z.B. RSS, UAH, GISS oder HadCRUT. Bei einigen dieser Datensätze wird in der Datenbank regelmäßig nachjustiert, was zu Stabilitätsproblemen der Daten führt. Das Gros der Datensätze wird in den USA und Großbritannien von einer kleinen Gruppe von Datenbankhütern betreut und verantwortet, was Fragen zur Transparenz aufwirft. Das bevölkerungsreichste Land der Erde, China, hat nun einen neuen globalen Temperaturdatensatz erstellt, der als CMA GLSAT bezeichnet wird. Dies steht für China Meteorological Administration Global annual mean Land-Surface Air Temperature. Der Datensatz wurde im Februar 2017 im Science Bulletin vorgestellt (Sun et al. 2017). Die Autoren weisen auf die starke Verlangsamung der Erwärmung in den letzten knapp zwei Jahrzehnten hin und stellen einen Bezug zum Hiatus her. Hier der Abstract:

Global land-surface air temperature change based on the new CMA GLSAT data set

The China Meteorological Administration (CMA) has recently developed a new global monthly homogenized land-surface air temperature data set. Based on this data set, we reanalyzed the change in global annual mean land-surface air temperature (LSAT) during three time periods (1901–2014, 1979–2014 and 1998–2014). The results show that the linear trends of global annual mean LSAT were 0.104 °C/decade, 0.247 °C/decade and 0.098 °C/decade for the three periods, respectively. The trends were statistically significant except for the period 1998–2014, the period that is also known as the “warming hiatus”. Our analysis generally confirms the spatial differences of global land warming over the two longer periods (since 1901 and 1979), as reported in previous Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment reports, but shows that the recent “warming hiatus” period was characterized by a slower warming or even a cooling trend in the low to mid-latitude zones of the two hemispheres.

Am 12. August 2017 erschien in den Geophysical Research Letters eine Arbeit von Clara Deser und Kollegen, die die Rolle des Pazifik für den globalen Hiatus bzw. Slowdown beleuchtete. Der Begriff „Hiatus“ erscheint dabei sogar im Titel der Arbeit. Die Forscher schicken zwei Klimamodelle an den Start, um den Hiatus zu reproduzieren. Die Resultate der Modelle waren jedoch höchst unterschiedlich, was die Modelle wenig vertrauenswürdig erscheinen lässt. Eines der beiden Modelle scheint jedoch auf den ersten Blick ganz gut mit der Realität zusammenzupassen. In diesem Modell dominiert die Abkühlung in Europa und Asien, die die globale Erwärmung bremst. Abstract:

The relative contributions of tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures and atmospheric internal variability to the recent global warming hiatus

The recent slowdown in global mean surface temperature (GMST) warming during boreal winter is examined from a regional perspective using 10-member initial-condition ensembles with two global coupled climate models in which observed tropical Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies (TPAC SSTAs) and radiative forcings are specified. Both models show considerable diversity in their surface air temperature (SAT) trend patterns across the members, attesting to the importance of internal variability beyond the tropical Pacific that is superimposed upon the response to TPAC SSTA and radiative forcing. Only one model shows a close relationship between the realism of its simulated GMST trends and SAT trend patterns. In this model, Eurasian cooling plays a dominant role in determining the GMST trend amplitude, just as in nature. In the most realistic member, intrinsic atmospheric dynamics and teleconnections forced by TPAC SSTA cause cooling over Eurasia (and North America), and contribute equally to its GMST trend.

Ein ähnliches Thema von Lukas von Känel und Kollegen im August 2017 in den Geophysical Research Letters:

Hiatus-like decades in the absence of equatorial Pacific cooling and accelerated global ocean heat uptake

A surface cooling pattern in the equatorial Pacific associated with a negative phase of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation is the leading hypothesis to explain the smaller rate of global warming during 1998–2012, with these cooler than normal conditions thought to have accelerated the oceanic heat uptake. Here using a 30-member ensemble simulation of a global Earth system model, we show that in 10% of all simulated decades with a global cooling trend, the eastern equatorial Pacific actually warms. This implies that there is a 1 in 10 chance that decadal hiatus periods may occur without the equatorial Pacific being the dominant pacemaker. In addition, the global ocean heat uptake tends to slow down during hiatus decades implying a fundamentally different global climate feedback factor on decadal time scales than on centennial time scales and calling for caution inferring climate sensitivity from decadal-scale variability.

In einigen Regionen der Welt beobachten die Wissenschaftler nicht nur einen Slowdown, sondern einen echten Hiatus, also eine wirkliche Erwärmungspause. Eine Gruppe um Yonkun Xie beschrieb im März 2017 im International Journal of Climatology den Hiatus aus China. Dabei überprüften sie, wie robust die chinesische Erwärmungspause der letzten beide Jahrzehnte wirklich ist. Die Forscher fanden eine signifikante Abkühlung in dieser Zeit, so dass der Hiatus als äußerst robust eingestuft wird. Xie und Kollegen machten sich auch Gedanken über den Antrieb der Erwärmung und nachfolgenden Abkühlung. Dabei kommen sie auf die Ozeanzyklen, die im späten 20. Jahrhundert erwärmend und im frühen 21. Jahrhundert kühlend wirkten. Eureka! Genau das stand ja auch schon 2012 in unserem Buch „Die kalte Sonne“, zu dem Jochem Marotzke seinerzeit sagte: „Viel gelesen aber wenig verstanden“. Mittlerweile ist es wohl auch Marotzke klar geworden, dass er damals irrte. Hier der Abstract der wichtigen Arbeit von Xie und Kollegen (2017):

From accelerated warming to warming hiatus in China

As the recent global warming hiatus has attracted worldwide attention, we examined the robustness of the warming hiatus in China and the related dynamical mechanisms in this study. Based on the results confirmed by the multiple data and trend analysis methods, we found that the annual mean temperature in China had a cooling trend during the recent global warming hiatus period, which suggested a robust warming hiatus in China. The warming hiatus in China was dominated by the cooling trend in the cold season, which was mainly induced by the more frequent and enhanced extreme-cold events. By examining the variability of the temperature over different time scales, we found the recent warming hiatus was mainly associated with a downward change of decadal variability, which counteracted the background warming trend. Decadal variability was also much greater in the cold season than in the warm season, and also contributed the most to the previous accelerated warming. We found that the previous accelerated warming and the recent warming hiatus, and the decadal variability of temperature in China were connected to changes in atmospheric circulation. There were opposite circulation changes during these two periods. The westerly winds from the low to the high troposphere over the north of China all enhanced during the previous accelerated warming period, while it weakened during the recent hiatus. The enhanced westerly winds suppressed the invasion of cold air from the Arctic and vice versa. Less frequent atmospheric blocking during the accelerated warming period and more frequent blocking during the recent warming hiatus confirmed this hypothesis. Furthermore, variation in the Siberian High and East Asian winter monsoon season supports the given conclusions.

Dazu passend eine Arbeit von Yang Chen und Panmao Zhai, die am 26. Juli 2017 online in den Environmental Research Letters publiziert wurde:

Persisting and strong warming hiatus over eastern China during the past two decades

During the past two decades since 1997, eastern China has experienced a warming hiatus punctuated by significant cooling in minimum temperature (Tmin), particularly during early-mid winter. By arbitrarily configuring start and end years, a „vantage hiatus period“ in eastern China is detected over 1998-2013, during when the domain-averaged Tmin exhibited the strongest cooling trend and the number of significant cooling stations peaked. Regions most susceptible to the warming hiatus are located in North China, the Yangtze-Huai River Valley and South China, where significant cooling in Tmin persisted through 2016. This sustained hiatus gave rise to increasingly frequent and severe cold extremes there. Concerning its prolonged persistency and great cooling rate, the recent warming hiatus over eastern China deviates much from most historical short-term trends during the past five decades, and thus could be viewed as an outlier against the prevalent warming context.

Der globale Hiatus war auch im August 2016 Thema in einer Arbeit von Chunlüe Zhou und Kaicun Wang im Nature-Ableger Scientific Reports.

Spatiotemporal Divergence of the Warming Hiatus over Land Based on Different Definitions of Mean Temperature

Existing studies of the recent warming hiatus over land are primarily based on the average of daily minimum and maximum temperatures (T2). This study compared regional warming rates of mean temperature based on T2 and T24 calculated from hourly observations available from 1998 to 2013. Both T2 and T24 show that the warming hiatus over land is apparent in the mid-latitudes of North America and Eurasia, especially in cold seasons, which is closely associated with the negative North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Arctic Oscillation (AO) and cold air propagation by the Arctic-original northerly wind anomaly into mid-latitudes. However, the warming rates of T2 and T24 are significantly different at regional and seasonal scales because T2 only samples air temperature twice daily and cannot accurately reflect land-atmosphere and incoming radiation variations in the temperature diurnal cycle. The trend has a standard deviation of 0.43 °C/decade for T2 and 0.41 °C/decade for T24, and 0.38 °C/decade for their trend difference in 5° × 5° grids. The use of T2 amplifies the regional contrasts of the warming rate, i.e., the trend underestimation in the US and overestimation at high latitudes by T2.

Cartoon: Josh.