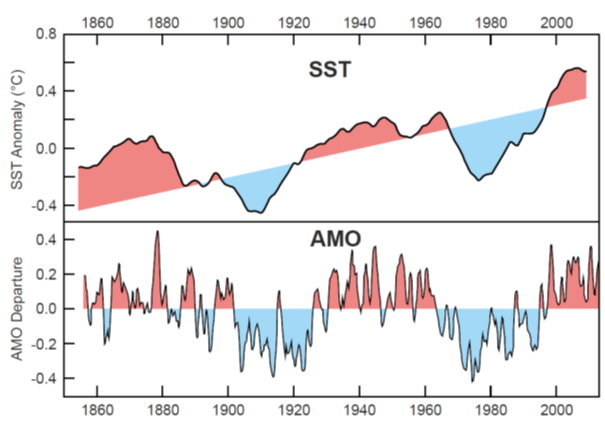

Die AMO ist ein bedeutender Ozeanzyklus, der mit 60-70 Jahren pulsiert. Nach mittlerweile mehr als zwei Jahrzehnten warmer AMO-Phase, schickt sich die „Atlantische Multidekaden Oszillation“ derzeit an, das Hochplateau zu verlassen und in den kommenden 5-10 Jahren in die negative Phase einzutauchen. Warum ist das wichtig? Die AMO übt einen wichtigen Einfluss auf die Temperaturen Europas aus, besonders im Sommer und in den Übergangsjahreszeiten. Hier ein Beispiel zum Verlauf der AMO und der Meeresoberflächentemperatur des Mittelmeeres (Jahreswerte):

Abbildung 1: Entwicklung der jährlichen Meeresoberflächentemperatur des Mittelmeeres (SST, Daten von Marullo et al. 2011) sowie der AMO. Abbildungsquelle: Lüning et al. 2019.

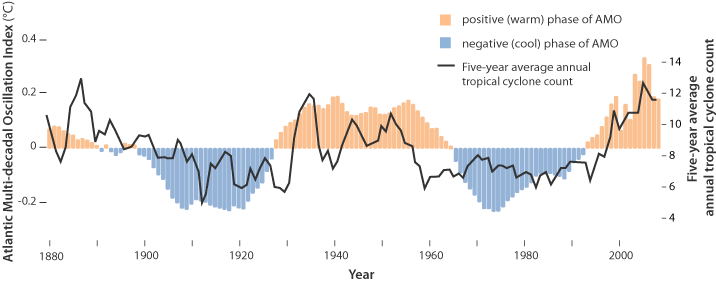

Überlagert ist ein Langzeittrend der letzten 150 Jahre. Wenn jetzt die AMO allmählich wieder absinkt, bedeutet dies für Europa, dass die Sommer der kommenden zwei Jahrzehnte tendenziell kühler ausfallen werden. Vermutlich wird es weniger Hitzewellen geben. Ron Lutz hat im April 2019 auf Science Matters die AMO näher beschrieben. Dabei zeigt er auch die gute Übereinstimmung der AMO mit der Häufigkeit tropischer Wirbelstürme im atlantischen Raum:

Abbildung 2: Vergleich von AMO und Häufigkeit tropischer Wirbelstürme. Quelle: Energy and Education Canada via Science Matters

Und nun kommt ein Fakt, der außerhalb der Fachzirkel wenig bekannt ist: Die AMO wird im Maßstab von Jahrzehnten offenbar zu einem Teil von der Sonnenaktivität gesteuert, zusammen mit Vulkanausbrüchen. Dies wurde von einer ganzen Reihe von Publikationen festgestellt, nachzulesen hier:

- Knudsen, M. F., B. H. Jacobsen, M.-S. Seidenkrantz, and J. Olsen, 2014: Evidence for external forcing of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation since termination of the Little Ice Age. Nature Communications, 5, 3323.

- Malik, A., S. Brönnimann, and P. Perona, 2018: Statistical link between external climate forcings and modes of ocean variability. Climate Dynamics, 50, 3649-3670.

- Muthers, S., C. C. Raible, E. Rozanov, and T. F. Stocker, 2016: Response of the AMOC to reduced solar radiation – the modulating role of atmospheric chemistry. Earth Syst. Dynam., 7, 877-892.

- Otterå, O. H., M. Bentsen, H. Drange, and L. Suo, 2010: External forcing as a metronome for Atlantic multidecadal variability. nature geoscience, 3, 688-694.

- Wang, J., B. Yang, F. C. Ljungqvist, J. Luterbacher, Timothy J. Osborn, K. R. Briffa, and E. Zorita, 2017: Internal and external forcing of multidecadal Atlantic climate variability over the past 1,200 years. Nature Geoscience, 10, 512.

Wie funktioniert’s? Gemäß den aktuellen Erkenntnissen folgt die negative Phase der AMO im Abstand von ca. 5 Jahren einem solaren Minimum. Der Extremwert der AMO geschieht etwa 17 Jahren nach dem solaren Auslöser. Allerdings scheint die Korrelation im Laufe der Zeit etwas zu wandern. Dies ist vermutlich ein Hinweis auf das Wirken nichtlinearer Vorgänge, die wir noch zu schlecht verstehen.

Hier der Abstract von Malik et al. 2018 aus dem Fachblatt Climate Dynamics:

Statistical link between external climate forcings and modes of ocean variability

In this study we investigate statistical link between external climate forcings and modes of ocean variability on inter-annual (3-year) to centennial (100-year) timescales using de-trended semi-partial-cross-correlation analysis technique. To investigate this link we employ observations (AD 1854–1999), climate proxies (AD 1600–1999), and coupled Atmosphere-Ocean-Chemistry Climate Model simulations with SOCOL-MPIOM (AD 1600–1999). We find robust statistical evidence that Atlantic multi-decadal oscillation (AMO) has intrinsic positive correlation with solar activity in all datasets employed. The strength of the relationship between AMO and solar activity is modulated by volcanic eruptions and complex interaction among modes of ocean variability. The observational dataset reveals that El Niño southern oscillation (ENSO) has statistically significant negative intrinsic correlation with solar activity on decadal to multi-decadal timescales (16–27-year) whereas there is no evidence of a link on a typical ENSO timescale (2–7-year). In the observational dataset, the volcanic eruptions do not have a link with AMO on a typical AMO timescale (55–80-year) however the long-term datasets (proxies and SOCOL-MPIOM output) show that volcanic eruptions have intrinsic negative correlation with AMO on inter-annual to multi-decadal timescales. The Pacific decadal oscillation has no link with solar activity, however, it has positive intrinsic correlation with volcanic eruptions on multi-decadal timescales (47–54-year) in reconstruction and decadal to multi-decadal timescales (16–32-year) in climate model simulations. We also find evidence of a link between volcanic eruptions and ENSO, however, the sign of relationship is not consistent between observations/proxies and climate model simulations.

Die Luftqualität in den USA ist ebenfalls von der AMO abhängig, wie Shen et al. 2017 dokumentierten:

Strong Dependence of U.S. Summertime Air Quality on the Decadal Variability of Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures

We find that summertime air quality in the eastern U.S. displays strong dependence on North Atlantic sea surface temperatures, resulting from large‐scale ocean‐atmosphere interactions. Using observations, reanalysis data sets, and climate model simulations, we further identify a multidecadal variability in surface air quality driven by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). In one‐half cycle (~35 years) of the AMO from cold to warm phase, summertime maximum daily 8 h ozone concentrations increase by 1–4 ppbv and PM2.5 concentrations increase by 0.3–1.0 μg m−3 over much of the east. These air quality changes are related to warmer, drier, and more stagnant weather in the AMO warm phase, together with anomalous circulation patterns at the surface and aloft. If the AMO shifts to the cold phase in future years, it could partly offset the climate penalty on U.S. air quality brought by global warming, an effect which should be considered in long‐term air quality planning.

Wann werden die Entscheider in Deutschland endlich die AMO in ihre Planungen einbeziehen? Noch immer werden regionale Klimaberichte in Deutschland herausgegeben, in denen dieser überaus wichtige Ozeanzyklus samt seiner klimatischen Auswirkungen fehlt…