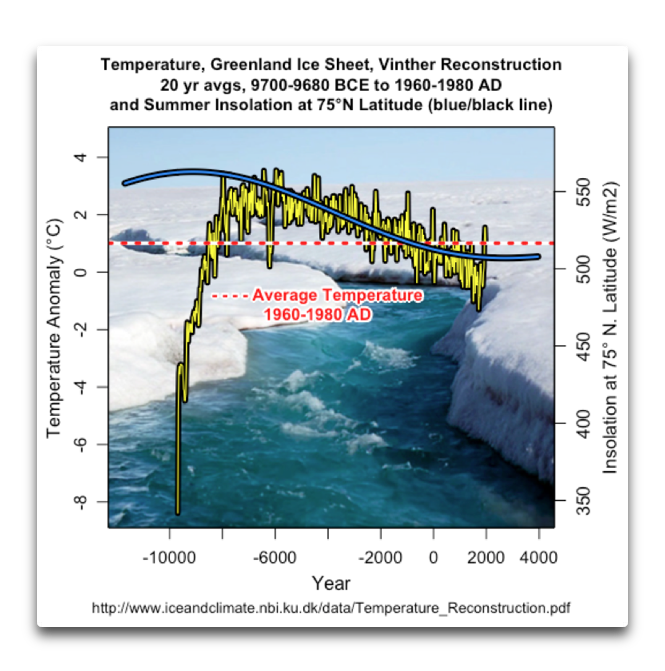

Die Vergangenheit ist der Schlüssel für die Zukunft. Wenn wir die vorindustrielle Klimageschichte und ihre natürlichen Antriebe verstehen, können wir auch die Klimazukunft besser prognostizieren. Willis Eschenbach hat auf WUWT einen Blick auf die Klimageschichte Grönlands während der vergangenen 12.000 Jahre geworfen. In seinem lesenswerten Kurzbeitrag erinnert er daran, dass die Durchschnittstemperaturen dort im Zeitraum von 8300-800 v. Chr. – also mehr als sieben Jahrtausende lang – oberhalb der Mitteltemperatur von 1960-1980 lag. Und selbst wenn wir die modernen Temperaturen aus dem 21. Jahrhundert verwenden, bleibt noch immer eine lange vorindustrielle Periode, während der es in Grönland wärmer war als heute. Hatten Sie das gewusst? Hier geht es zum WUWT-Grönlandartikel.

Abbildung: Temperaturentwicklung des grönlandischen Eisschildes auf Basis von Eiskerndaten (Renland and Agassiz, Vinter et al. 2009). Abilldung: Eschenbach/WUWT.

—————

Anastasios Tsonis ist ein Klimaforscher, der im Laufe seiner Karriere über 130 begutachtete Fachartikel schrieb sowie neun Bücher verfasste. Nun ist er pensioniert. Das heißt auch, dass er nun nicht mehr den Zwängen des offiziellen Wissenschaftsbetriebs unterliegt und frei sprechen kann. Und genau dies tat er am 2. Januar 2019 in einem ausgezeichneten Meinungsbeitrag der Washington Times:

The overblown and misleading issue of global warming

Very often, when I talk to the public or the media about global warming (a low-frequency positive trend in global temperature in the last 120 years or so), they ask me the unfortunate question if I “believe” in global warming. And I say “unfortunate” because when we are dealing with a scientific problem “believing” has no place. In science, we either prove or disprove. We “believe” only when we cannot possibly prove a truth. For example, we may “believe” in reincarnation or an afterlife but we cannot prove either.

[…]

Nobody argues that the temperature of the planet is not increasing in the last 120 years or so. Yes, the temperature is increasing overall. But there are a lot of questions regarding why that is.

In the current state of affairs regarding global warming, opinion is divided into two major factions. A large portion of climate scientists argues that most, if not all, of the recent warming is due to anthropogenic effects, which originate largely from carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels. Another portion is on the other extreme: Those who argue that humans have nothing to do with global warming and that all this fuss is a conspiracy to bring the industrial world down. The latter group calls the former group “the catastrophists” or “the alarmists,” whereas the former group calls the latter group “the deniers.” This childish division is complemented by another group, the “skeptics,” which includes those like me who question the extreme beliefs and try to look at all scientific evidence before we form an opinion (by the way, the former group also considers skeptics to be deniers).

[…]

The fact that scientists who show results not aligned with the mainstream are labeled deniers is the backward mentality. We don’t live in the medieval times, when Galileo had to admit to something that he knew was wrong to save his life. Science is all about proving, not believing. In that regard, I am a skeptic not just about global warming but also about many other aspects of science.

All scientists should be skeptics. Climate is too complicated to attribute its variability to one cause. We first need to understand the natural climate variability (which we clearly don’t; I can debate anybody on this issue). Only then we can assess the magnitude and reasons of climate change. Science would have never advanced if it were not for the skeptics. All model projections made for the 21st century failed to predict the slowdown of the planet’s warming despite the fact that carbon dioxide emissions kept on increasing. Science is never settled. If science were settled, then we should pack things up and go home.

Ganzen Beitrag in der Washington Times lesen.